Why I Write About Home

Or: Why did a feminists' daughter become so preoccupied with homemaking?

When I was a kid, I learned to distrust women who paid too much attention to the state of their homes. A tidy home was a boring home, I was subtly reminded, as we moved home-made puppets and stacks of drawing paper off the table so we could eat dinner. Evidently there were far better things to do than clean and fluff cushions all day.

Our home wasn’t particularly tidy, and it wasn’t a boring one either. With two parents who worked from home more often than not, I knew how to pave my way out of boredom by digging deep into my imagination whilst my parents scratched away in a studio that was technically the airspace between their bedroom and the bathroom. We lived in a very small house and it was filled to the gills with stuff, and then my sister was born and it was also filled with baby stuff.

All told, we had made a fine home together, but no-one living there would have ever called themselves a homemaker. I was raised in a feminist household that bucked a fair number of the social norms of the 1980s and ‘90s. I had a mother who worked, a father who cooked, and two married parents with different surnames who equally tended to their children’s needs. So it goes that my parents assumed joint responsibility for maintaining our home. This had the effect of both neutralising any gendered expectations of who would be pushing the vacuum around at our place, and presenting housework as something no one with any wit about them would actually choose to do.

Contrary to the prevailing narrative of the time which firmly placed women in traditional homemaking roles, I learned that women with some sense about them didn’t keep home. After years—centuries—of women being confined to small lives within domestic walls and quite often losing their minds as a result, my mother’s generation of feminist activists had walked the sisterhood out of the house and expressed no desire to return. To willingly cook or clean or press laundry was to actively participate in your own enforced labour. It was a lesson that ran deep.

Now that I have two small children of my own, and I live and work in a very small home, I understand the futility of trying to keep things clean and tidy. My children also have a mother who works, a father who cooks, and two married parents with different surnames who equally tend to their children’s needs. I’m well-versed in the contemporary language around the mental load, and the research which shows that women in heterosexual relationships perform far more housework than their male partners, on average. I know that in the year 2025, a full four decades after my parents brought me back from the hospital to a home they had both cleaned, homemaking is still a heavily gendered activity that centres on women. I know that being a housewife is an occupation whilst being a househusband is a joke.

I agree that there are far better things to do than clean one’s home all day. And whilst I certainly don’t clean all day, I do clean every day. I even fluff my cushions. All told, I have gone so far as paying quite a lot of attention to the state of my home. And not just mine—I pay attention to the state of thousands of people’s homes, whether they even know it or not.

What took place in the years between then and now is a kind of unlearning, I suppose. A recalibration of home and identity as it pertains to me, specifically, and to women and men generally. To use a metaphor closer to home, it’s been a process of looking at this edifice of received wisdom—the house built on experiences that were not my own—and realising that it was no longer fit for purpose. I needed to pull it to the ground and rebuild, brick by learned brick, the sturdy foundations and walls that reflect what I actually know and feel. Like all great renovations, it feels like the work of a lifetime. It has become my living, no less.

The question I try to answer for myself is this: Why did the feminist’s daughter who scoffed at the women whose occupation was homemaker become so singularly occupied with homemaking?

This is why I write about home.

***

About six years ago, when I was pregnant with my daughter, I recruited someone to join my newly established team of Life at Home communicators at IKEA. Amongst other things, we would be in the lead for the rapidly growing Life at Home Report—an extensive piece of global qual and quant research that was redefining what we thought we all knew about home.

When I took stock of all the applications received—more than 200—I realised that only two (2) of them were from men. All the rest were from women. There are likely a number of systemic biases underneath this significant gender skew, including the fact that the hiring manager was a woman (me), but I just couldn’t shake the thought that the very mention of ‘home’ signalled that this was a woman’s job.

It made me livid. And then it made me sad. And then—finally—it made me focussed.

I have known for a long time that the way we feel about home impacts on the way we show up in life. I’d known it in a visceral way for many decades until I had the extraordinary opportunity to lead the world’s largest piece of research into exactly this. And now I know it in a fundamental way, from the data and insights and home visits that create new perspectives and vocabulary for this feeling we all share—the feeling of home. The research shows that people who feel more positive about their home also feel more positive about their future; and that people who make proactive choices about the interiors of their home report better mental health outcomes at the same time.

What’s also apparent is that women possess no greater flex for the ‘feeling of home’ or harbour a different set of emotional needs about home, compared to men. There is nothing in the research which indicates that home—the place and the feeling—is in any way more relevant for women than men. We all have the capacity to create a vibrant domestic life.

And yet society persists with this blind spot that the home is, by default, the woman’s domain. It’s as if the idea of anything domestic cannot possibly be serious or meaningful or game-changing enough to capture the attention of ambitious men. Isn’t it funny how a Swedish multi-billion Euro company has successfully shown the opposite to be true…? And yet society stumbles on.

It still makes me mad, but when I got focussed I realised that it’s an extraordinary thing to be able to look at your own life through the lens of a research study—we aren’t all gifted that kind of chance for introspection. These are the keys to the kingdom. Or at least the keys to a new home. Slowly but surely I am building that new home from everything I learn. I don’t have many practical skills, but I can write—so I use words and stories to make something which I believe is better for me and my family. In time, I believe this new kind of home can house us all.

This is why I write about home.

***

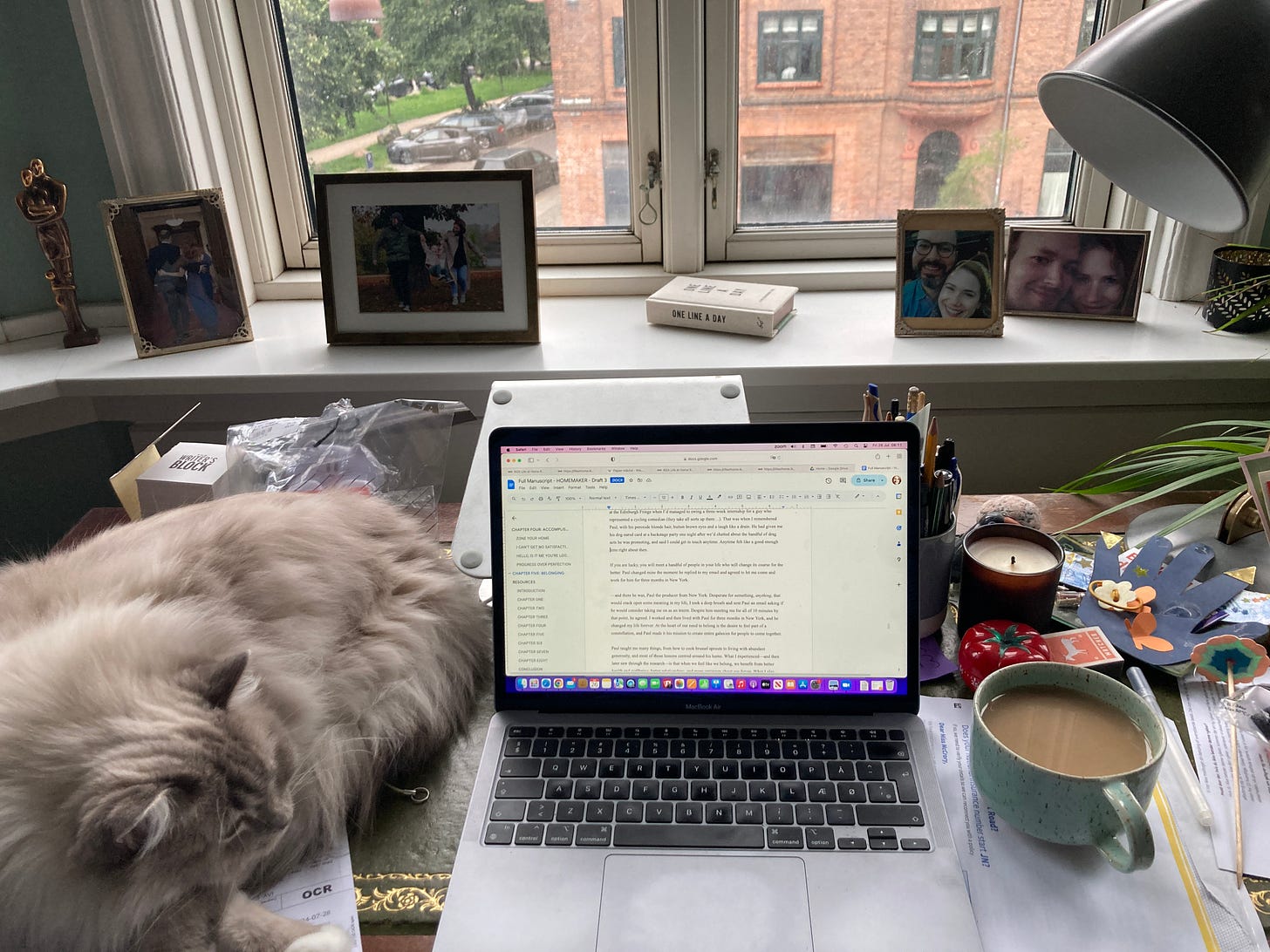

I’ve applied the research to my own life at home, time and time again. In the years since I began leading this work, I’ve had two children whilst continuing to live in the same 90-square-metre apartment with my husband and our large (and very entitled) housecat. The footprint of our home has not changed one inch, but our life there has grown in magnificent and—sometimes—painful ways. I have had to reckon with a lot of big feelings about this alongside managing the practical aspects of small-space living.

This growth has taught me that many daily functional aspects of homemaking—such as cleaning and cooking—are deeply emotional. This can pull in all kinds of directions ranging from hard and sad feelings like shame and rage to the very substance of living, like love. I have learned that you get to choose how you show up in your own life at home, and that there are no absolutes. A tidy home doesn’t mean it’s a boring one, when keeping things tidy means you are realising comfort, control, accomplishment, nurturing or belonging. I tidy my home because I have better things to do—like write about it.

The kind of work I do in the arena of life at home is hard to capture in a single image. I’m not an interior designer or an architect; I don’t do (much) DIY or know how to assemble IKEA furniture any quicker than a random person on the street. I don’t have home renovation projects on the go to document, and I don’t post photos on social media of the way I’ve styled a bookcase or coffee table with just the right light and colours and angles.

If you show me a beautiful chair, I want to know about the person who was last sitting in it. If you show me a stunning tablescape for Christmas, I want to know about the arguments in the kitchen whilst people are cooking the food. I love the pretty things too, but I know—from the research and my lived reality—that behind everything which is curated for us to see sit lots and lots of feelings. That’s what I love to explore and share with the world. The kind of work I do is precisely the kind of work that is best served by words, not images.

This is why I write about home.

***

To date, I have written hundreds of thousands of words about home across a full manuscript, my work, and the various newsletters I share here. I believe there is no limit to what can be written about home precisely because there is no limit to what home can do for people. When I’m occupied with homemaking, I’m occupied with life. Those of us with a roof over our heads get to make a decision every day about the quality of the life we live at home. By doing so, we’re making a choice about how we live the rest of our lives. Homemaking isn’t an occupation for certain kinds of people but an action we all participate in.

On this, I’m going to let my husband have the last word. He once wrote something magical about baking granola with our daughter, and he seemed to capture the whole of my work in one, tender line. My husband was brought up in a tidy house where life at home fell along traditional gender lines, and I marvel at his capacity to unlearn and relearn alongside me, as we raise our kids and make a home together. He knows, just as he wrote, “Because home isn’t just where you live—it’s something you create, over and over again.”

It’s something you create, over and over again.

This is why I write about home.

If you live near Malmø in Sweden, I’m delighted to say that I’m hosting my Sweden book launch for WHERE THE HEART IS at Elsewhere, the brilliant new English-language bookstore on Davidshallsgatan, on February 27th from 6pm. You can find the fine folks at Elsewhere here and you can also find information about the event and where to RSVP here. Hejdå!

More details to come about Copenhagen and London events soon…